- Home

- George R. Elford

Devil's Guard Page 2

Devil's Guard Read online

Page 2

Our headquarters had ordered us: "Stay where you are and hold the pass." Then our headquarters returned to Germany. Like the Roman sentry who had stood his guard while Vesuvius buried Pompeii, we too remained soldiers to the bitter end.

We had survived the greatest war in history, but if we were to survive peace, the most bloodthirsty peace in history, we had to reach the American lines two hundred miles away. Not because we thought much of American chivalry but at least Americans were Anglo-Saxons, civilized and Christian in their own way. Around us in the valley were only the Mongolian hordes, the Tatars of a mechanized Genghis Khan—Stalin. I had the notion that it was only a choice between being clubbed to death by cavemen or submitting to a more civilized way of execution.

To reach Bavaria and the American lines we had to cross the Soviet-controlled Elbe. We were still confident of our own strength. We had survived more hell than could possibly wait for us on the way home. German soldiers do not succumb easily. We could be defeated but never crushed.

All day long Captain Ruell of the artillery had been trying to reach the headquarters of Field Marshal Schoerner. No one acknowledged his signals but finally he did manage to contact General Headquarters at Flensburg. I was standing close to him and saw his face turn ashen. When he lowered his earphones he was shaking in every limb and could barely form his words as he spoke: "It's the end. . . . The Wehrmacht is surrendering on all fronts. . . . Keitel has already signed the armistice. . . . Unconditional surrender." He wiped his face and accepted the cigarette which I lighted for him. "The Fatherland is finished," he muttered, staring into the distant valley with vacant eyes. "What now?"

Suddenly it dawned on us why the Russians had refrained from forcing the pass. The Soviet commander had known that the war was about to end, and he did not feel like sacrificing his troops only minutes before twelve o'clock. But he v/as aware of our presence in the neighborhood. Within six hours after the official announcement of the German capitulation, Soviet PO-2's appeared overhead. Circling our positions the planes dropped a multitude of leaflets announcing the armistice. We were requested to lay down our weapons and descend into the valley under a flag of truce. "German Officers and Soldiers," the leaflets read, "if you obey the instructions of the Red Army commander you shall be well treated, you will receive food and medical care due to prisoners of war, according to the articles of the Geneva Convention. Destruction of war material and equipment is strictly prohibited. The local German Commander shall be responsible for the orderly surrender of his troops."

Had our plight not been so bitterly serious we could have sneered at the Russians quoting the Geneva Convention, something the Kremlin had neither signed nor acknowledged. The Red Army could indeed promise us anything under the articles of the Convention; it was not bound by its clauses.

The following morning our sentries spotted a Soviet scout car as it labored uphill on the winding road to our positions. From its mudguard fluttered a large white flag of truce. I ordered my troopers to hold their fire, and called a platoon for lineup. Everyone was shaved and properly dressed. I wanted to receive the Soviet officers with due respect. I was astonished to see the car stop three hundred yards short of our first roadblock, and, instead of sending forward parliamentaries, the enemy began to deliver a message through loudspeakers.

"Officers and soldiers of the German Wehrmacht. . . . The Soviet High Command knows that there are Nazi fanatics and war criminals among you who might try to prevent your accepting the terms of armistice and consequently your return home. Disarm the SS and SD criminals and hand them over to the Soviet authority. Officers and soldiers of the Wehrmacht. . . . Disarm the SS and SD criminals. You will be generously rewarded and allowed to return home to your families."

"The filthy liars!" Untersturmfuhrer Eisner sneered, watching the Russian group through his binoculars. "They will be allowed to return home! That is a good joke."

It was amusing to note how little the enemy knew the German soldier. After having fought us for so many' years, the Soviet High Command should have known better. Cowardice or treason was never the trade of the German soldier. Nor was naivete. They had called us "Fascist criminals" or "Nazi dogs" ever since "Operation Barbarossa." In the past they had made no distinction between the various services. Wehrmacht, SS, or Luftwaffe had always been the same to Stalin, yet now he was endeavoring to turn the Wehrmacht against the SS and vice versa.

The loudspeakers blared again. Eisner pulled himself to attention. "Herr Obersturmfuhrer, I request permission to open warning fire."

"No! Nothing of the sort, gentlemen," Colonel Stein-metz, the commanding officer of the small motorized infantry group protested. "We shouldn't fire at parliamentaries."

"Parliamentaries, Herr Oberst?" Eisner exclaimed with a bitter smile. "They are sheltering behind the flag of truce to deliver Communist propaganda."

"Even so," the colonel insisted. "We may request them to withdraw but we should not open fire."

Being an officer of the Wehrmacht, Colonel Steinmetz had no authority over the SS. He was, however, a meticulously pedantic officer and much our senior both in rank and age. I did not feel like entering into futile arguments, especially in front of the ranks. Trying to avoid the slightest offensive quality in my voice I reminded him that I was in charge of the pass and all the troops therein. Even so the colonel stiffened at my remark and said, "I am aware of your command. Herr Obersturmfuhrer, and I hope you will handle the situation with the responsibility of a commander."

The Russian loudspeakers kept blaring. Eisner shrugged and began to observe the enemy again. I exchanged glances with Erich Schulze and saw defiance in his eyes. Both men had been my comrades for many years. Bernard Eisner had been my right hand since 1942. He was a cool and hard fighter. Having been well-to-do landowners, Eisner's father and elder brother had been beaten to death by a Communist mob during the short-lived "proletarian revolution" after the First World War. It was Bernard's conviction that no Communist on earth should be left alive. Schulze, who had joined my battalion in 1943, was rather hotheaded but always polite and considerate.

A few steps from where we stood two young troopers sat behind a heavy machine gun, which they kept trained on the Soviet scout car. Their faces were tense but lacking emotion, as though they were statues or a part of the gun. Both were young, only nineteen years old. Drafted in 1944, they had not experienced the real trials of the war.

I asked for a loudspeaker and addressed the Russians:

"This is the German commander speaking. We have not received an official confirmation of the armistice and we will hold our positions until such confirmation can be obtained. I request the Soviet commander to furnish an authentic document related to the question of armistice. I also request that, in the meantime, the Soviet propaganda unit refrain from using the flag of truce for communicating subversive propaganda. I request that the Soviet propaganda unit withdraw from our positions within five minutes. After five minutes I shall no longer consider them immune to hostilities."

"German officers and soldiers. . . . Disarm the SS and SD criminals and hand them over to the Soviet authority.

You shall be generously rewarded and allowed to return home."

"I request that the Soviet propaganda unit refrain from using the flag of truce for communicating subversive propaganda," I repeated. There was a pause; then the loudspeakers blared once more. "German officers and soldiers. .. . Disarm the SS and SD criminals. , .."

I ordered, "Fire!"

The scout car burst into flames, then exploded. When the smoke and dust settled we saw two Red army men scurrying down the road. "That should fix them for the time being," Eisner remarked, lighting a cigarette. "Bullets are the only language they understand."

An hour later a squadron of Stormoviks dived out of the clouds with the intention of strafing and bombing our positions. To reach us, however, the planes had to come in level between a cluster of high cliffs, then drop sharply over the small plateau which we occupie

d. The Russian pilots flew well, but they had bad luck. I had deployed eight 88's and ten heavy MG's to cover that narrow corridor and our gunners were experienced men. Within a few minutes five of the • planes had been shot down. Trailing smoke two more had escaped toward the valley and a third one had banked straight into a three-hundred-foot rock and exploded, fuel, bombs, ammunition and all. At that point the four remaining planes had given up and departed without having fired a shot. We spotted two Soviet pilots parachuting downward. One of them hit a cliff, slipped his chute, and tumbled to his death at the bottom of a ravine. The other one, a young lieutenant, landed right on one of our trucks. He was made prisoner.

"Zdrastvuite, tovarich!" Captain Ruell, who spoke impeccable Russian, greeted our astonished visitor.

My men searched the pilot. I looked into his identification book but handed it back to him. And when Schulze gave me the officer's Tokarev automatic, I only removed the bullets and returned his gun as well. He was so surprised at my unexpected behavior that his chin dropped. He tried to smile but he could not. He only managed to draw his lips in a paralytic grin.

"The war is over," he muttered. "No more shooting," he added after a moment, imitating the sound of a submachine gun. "No tatatata." His face showed so much

terror that we could not help smiling. He must have been told that Germans were man-eaters.

"No more tatatata, eh?" Erich Schulze chuckled, mocking the Russian.

The pilot nodded quickly. "Da, da. . . . No more war."

Schulze poked him in the belly. "No more war but a minute before you wanted to bomb the daylight out of us here."

"la, ja," the Russian repeated, his eyes glued to Schulze's SS lapel.

Erich poked him gently again, and the Russian paled.

"Leave him alone," Captain Ruell interposed. "You are scaring the shit out of him."

"Sure," Eisner added, "and we don't have many extra pants up here, Erich."

The captain spoke to the pilot briefly and his presence seemed to lessen the Russian's fear. "Don't let the SS shoot me, officer," he pleaded. "I have been flying for only eight months, and I want to go home to Mother."

"We have been fighting for five years. Imagine how much we would like to return home," Captain Ruell replied with a bitter smile.

"Don't let the SS shoot me. .. ."

"The SS won't shoot you."

Schulze offered the Russian a cigarette. "Here, smoke! It will do you good."

"Thanks." The pilot grinned, taking the cigarette with shaking fingers.

Erich opened his canteen, gulped some rum, then wiped the canteen on his sleeve and offered it to the pilot. "Here, tovarich. .. . Drink good SS vodka."

Realizing that his life was not in danger the Russian relaxed.

"Our commander says that you don't want to surrender," he said, shifting his eyes from face to face as though seeking our approval for what he was saying. "You must surrender. . . . There are two divisions in the valley; forty tanks and heavy artillery are expected to come in a day or two."

"Tovarich, you have already told us enough for a court-martial," Schulze exclaimed, slapping the pilot on the back.

"You shouldn't tell the enemy what you have or don't have." Captain Ruell interpreted for him.

"I only said that heavy artillery is on the way."

"Who cares?" Eisner shrugged. "There is a mountain between your artillery and us."

"The mountain will not help you." The Russian shook his head. He turned and pointed toward a ridge five miles to the southeast. "The artillery is going up there."

"Nonsense!" I said. "There is no road."

"There is a road," Captain Ruell interposed, "right up to hill Five-O-Six. We had four Bofors there in early March."

Looking at the map I realized that Captain Ruell was right and what the Russian pilot was saying had a ring of truth. Should the Soviet commander mount some heavy artillery on that hill, he could indeed shell our plateau by direct fire.

We gave the Russian a hearty meal and allowed him to leave. He was immensely happy and promised to do everything for us should we meet again after surrendering. "Food, vodka, cigarettes, Kamerad. My name is Fjodr Andrejevich. I will tell our commander that you are good soldiers and should be well treated."

"Sure you will," Eisner growled, watching the Russian leave. "You just tell your commander and you will be shot before the sun is down as a bloody Fascist yourself."

The pilot walked away slowly, turning back every now and then as though still expecting a bullet in the back. Having passed our last roadblock it must have occurred to him that he was still alive and unhurt, and he began to race downhill as I had never seen a man run. Eisner was not very enthusiastic about the Russian's departure.

"He saw everything we have up here," he remarked with barely concealed disapproval in his voice.

"We had no choice but to let him go," Colonel Steinmetz challenged him sharply. "The war is over, Herr Untersturmfuhrer,"

"Not for me, Herr Oberst," Eisner replied quietly. "For me the war will be over when I greet my wife and two sons for the first time since August 1943, and it isn't over for the Russian either. He came here flying not the white flag but a fighter bomber."

"I haven't seen my family since June 1943," the colonel remarked.

I drew Eisner aside. "You should not worry about the Ivan," I told him with an air of confidence. "What can he tell? That we have men, weapons, tanks, and artillery? The more he tells the less eager they will be to come up here." I put an arm around his shoulder. "Bernard, we've killed so many Russians. We can surely afford to let one individual go."

He grinned. "I have read somewhere what the American settlers used to say about the Indians, Hans. The only good Indian is a dead Indian. I think that is also true of the Bolsheviks."

"Maybe the pilot was not a Bolshevik?"

"Maybe he wasn't—yet. But if you ask me, Hans, I can tell you that anyone who is working for Stalin is game for me." He lit a cigarette, offered me one, then went on. "I know that we are defeated and that there will be no Fatherland to speak of for a long time to come. For all we know the Allies might break up the Reich into fifty little principalities, just as it was five hundred years ago. We scare them stiff, even without weapons, even in defeat. But I cannot suffer the thought of having been defeated by a rotten, primitive, lice-ridden Communist mob. I know that no conqueror in history was ever soft on the conquered enemy. We might survive the American and the British but never the Soviet. Stalin won't be satisfied with what he may loot now. He will not only take his booty, but he will try to take our very souls, our thoughts, our national identity. I know them. I've been their prisoner. It was for only five days but even then they tried to turn me into a bloody traitor. The Russians are mind snatchers, Hans. They will not only rape our women, they will also turn them into Communists afterwards. Stalin knows how to do it and now he will have all the time on earth. He is going to increase the pressure inch by inch. I could gun down anyone who is helping Stalin."

"You would have quite a few people to gun down, Bernard. Starting with the British and finishing with the Americans. They have not only helped Stalin, but also brought him back from his deathbed and made him a giant."

"Stalin will be most obliged to his bourgeois allies," Eisner sneered. "Just wait and see how Stalin will pay for the American convoys. Give him a couple of years. Mister Churchill and Mister Truman are going to enjoy a few sleepless nights for Mister Roosevelt's folly."

"That won't help us much now, Bernard!"

"I guess not," he agreed- After a brief pause he added, "If you decide to surrender, Hans, just let me have a gun and a couple of grenades. I will find my way home."

"You won't be alone." I gave him a reassuring tap. "I don't feel like hanging in the main square of Liberec, either."

"I don't feel like submitting myself to what comes between the surrender and the hanging," he added with a sarcastic chuckle.

Early in the afternoon the PO-2's

returned, but we did not fire on the flimsy canvas planes which carried no weapons. The Russians had sent us another load of leaflets, among them newspaper cuttings announcing the armistice, and photocopies of the protocol bearing the signature of General Field Marshal Keitel. Again we were requested to lay down our weapons and evacuate into the valley under the flag of truce.

"This is it!" Colonel Steinmetz spoke quietly as he crumpled the Soviet leaflet between his fingers. "This is it!" And as though providing an example, he unbuckled the belt which supported his holster, swung it once, and tossed the belt on a flat slab of stone. I expected nothing else from Colonel Steinmetz. He was a meticulously correct officer, a cavalier of the old school who would always keep to the letter of the service code. He could see no other solution but to comply with that last order of the German High Command, or what was left of it. Moving like automatons, his three hundred officers and men began to file past our sullen group, the troops casting their rifles and sidearms onto the mounting pile. But the artillery, the small panzer detachment, and the Alpenjaegers kept their weapons, and, with a skill born of habit, the SS took over the vacated positions.

"I am sorry," Colonel Steinmetz said quietly, and I noticed that his eyes were filled. "I cannot do anything else."

"There is no longer a high command, Herr Oberst, and the Fuehrer is dead. You are no longer bound by your oath of allegiance," I reminded him.

He smiled tiredly. "If we wanted to disobey orders we should have done it a long time ago," he said. "Right after Stalingrad. And not on the front but in Berlin."

"You mean a successful twentieth of July, Herr Oberst?"

"No," he shook his head. "I think what Stauffenberg

did was the gravest act of cowardice. If he was so sure of doing the right thing, he should have stood up, pulled his gun, shot Hitler, and taken the consequences. But I don't believe in murdering superior officers. The Fuehrer should have been declared unfit to lead the nation and, removed. Had Rommel or Guderian taken command of the Reich, we might have won—if not the war, at least an honorable peace."

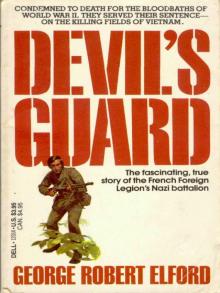

Devil's Guard

Devil's Guard